November 11, 1996

Every match day thousands of Liverpool fans file past the every buildings in which their beloved club was born.

But ask any of them to point out those footballing landmarks and the chances are you will find them stuck for an answer.

For while the origins of Liverpool Football Club are well-documented, the stage on which the dramatic split with Everton was played out in 1892 has rarely been remembered.

No plaques mark the spots where the meetings and wranglings took place, where the earliest games were played and where the decision to set up the new club was taken.

Even the guide-books of the city’s booming heritage industry, which can take you on a tour of the Anfield stadium itself, ignore the places where Merseyside’s rich football history began.

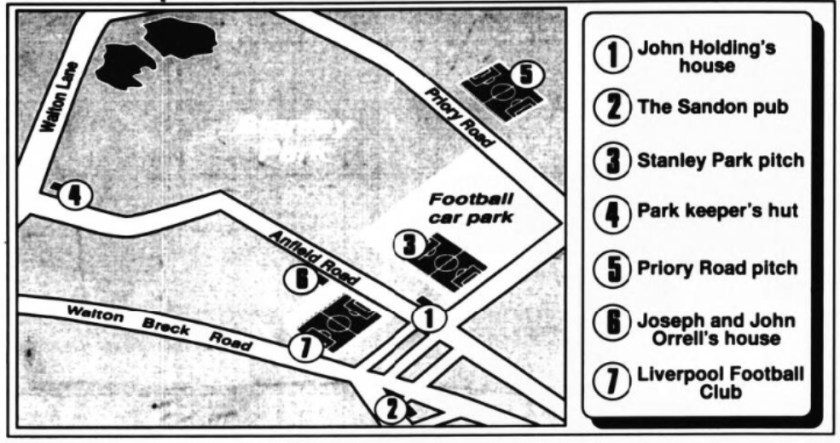

The home of John Houlding, once the “King of Everton” and then the founder of Liverpool, sits unnoticed in Anfield Road. The old Sandon pub that he owned and which acted as the first headquarters of both clubs lies unused and boarded up. The first pitch ever used by the Everton side from which Liverpool emerged is buried beneath Stanley Park’s football car park, while the house of Anfield’s first owner made way for the Reds’ old souvenir shop many years ago.

And that, believe Dr John Rowlands, one of the few people to have researched the physical origins of the club, is both a surprise and a shame.

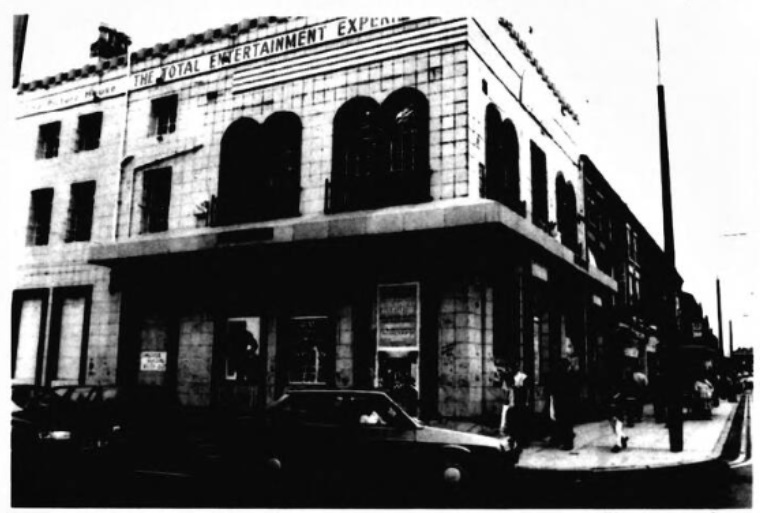

The Maghull GP, who is a member of the Association of Football Statisticians, says: “John Houlding’s house is still the same as it was when he was alive and the Sandon pub, which later became the Picture House, was still in use on the corner of Houlding Street and Oakfield Road until recently.”

And he adds: “Stanley Park is very much as it was in the 19th century, and every time I go through it I can imagine playing there.

And he adds: “Stanley Park is very much as it was in the 19th century, and every time I go through it I can imagine playing there.

“You could bring someone back from a hundred years ago and they would find that the area looks pretty much the same as it did then.”

“I’ve often thought there should be a walking tour of all the sites, and I’m surprised that there has never been a plaque to ark John Houlding’s house or that the club never named a stand after him. But I suppose all clubs live for today and tend not to look that far back into their pasts.”

Arkles Lane.

At the vert beginning of the past, Liverpool were of course Everton, the side which has emerged from St. Domingo Church F.C. in 1878. The new club’s first year were spent playing on a pitch in the south-west corner of Stanley Park, near its border with Arkles Lane.

Members had to mark out the pitch themselves and carry the goalposts the entire length of Anfield Road, from the park keeper’s lodge at the far end.

By 1883, the side had become successful enough to attract up to 2,000 spectators, none of whom could be charged for admission because the games were staged in a public park.

So for the 1883-84 season, the club moved across Priory Road to land bordering a house called Coney Green owned by William Cruitt, a wealthy cattle salesman, to free itself from the constraints of the park regulations.

But, as Dr Rowlands recalled, it wasn’t just admission fees that were an issue. He says: “One of the main reasons they left was that as they got bigger they wanted to start playing earlier in the year, but the rules of Stanley Park insisted that the cricket season went on until September and that no football could be played before then.

“As they became more important, the club thought they should be able to play whenever they liked.”

Cemetery.

But the next summer, Anfield was born after William Cruitt refused the club permission to carry on using his land, apparently because the crowds were too noisy for his liking. The pitch is now covered by part of the Anfield cemetery and the petrol station on Priory Road.

John Houlding, a brewer who was then president of Everton was instrumental in turning the cricket pitch that existed in Anfield Road into a new home for his team. Houlding took up the tenancy from the ground’s owners, fellow brewers Joseph and John Orrell, whose own Anfield Road house extended into today’s club car park where the old souvenir shop now stands.

The pitch was railed off and the field turned into a football ground, including “a very humble stand crouching on the east side for officials, members, pressmen and affluents.”

By 1892, Houlding had bought the ground from the Orrells and was now the landlord of Everton, who were still based in his nearby Sandon Hotel.

But a dispute over the rent he wanted to charge the club that year caused them to walk out and set up home at what is now Goodison Park, leaving Houlding to establish his own club, Liverpool, to play on the existing ground.

Dr Rowlands says: “Everton moved out of the Sandon and Liverpool almost certainly moved in straight away, because Houlding still owned the pub.”

The Sandon.

Like several of the other city pubs owned by Houlding, who was also Lord Mayor of Liverpool, the Sandon is still standing, on the corner of Houlding Street – the only recognition of Liverpool’s founder in the whole district – although it is no longer in use.

Houlding’s home, however, remains much as it was in the late 1800s when his interest was captured by the football matches taking place on the park beyond his rear garden wall.

Houlding’s home, however, remains much as it was in the late 1800s when his interest was captured by the football matches taking place on the park beyond his rear garden wall.

Stanley House now belongs to Ike and Violet Williams, who are only the second people to own it since the building was in Houlding’s hands.

Mr. Williams, 77, was sold the large property in 1953 by a glass merchant called Greenberg, whose family firm is still going strong in the city and who had bought the house from Houlding himself.

The scale of the Victorian building, which has more than 20 rooms, is still as imposing today as it was when Houlding paced its halls and held the conversations that led to the formation of Liverpool more tan a century ago, and reveals just how wealthy the club’s first benefactir must have been.

Marble fireplaces dominate the rooms whose high ceilings are bordered by ornate coving carved into the shape of leaves and fruit. But most impressive is the engineering feat that drove a steel girder through the middle of the house in order to support the weight of a snooker table Houlding installed on the top floor.

Remains.

Mr. Williams, a retired joiner, says: “He left the table to Mr. Greenberg, who said I could have it and try to sell it. No-one seemed to be interested so in the end I scrapped it and made a work bench out of it,

The remains of Houlding’s snooker table now sit covered in sawdust in the old coach house that doubles as Mr. Williams’ workshop, beneath the original wooden racks on which the football pioneer would hang his horses’ collars and tack.

“He had the money to have the best,” says Mr. Williams, “and the house hasn’t changed much over the years.”

Houlding’s house, and the pub in which the club began, may have stood the test of time, but official recognition of their pivotal role in Liverpool’s history has never been forthcoming.

And, as Mr. Williams says: “I’m surprised that nothing has ever been done to remember John Houlding. It’s a shame really because these are the roots of Liverpool Football Club and they shouldn’t be forgotten.”

(Source: Liverpool Echo: November 11, 1996; via http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) © 2018 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited